I. Intro

Hello! Welcome to my presentation “The Art of Collaboration,” where I’ll talk about how to cultivate successful and rewarding collaborations. I’ll be discussing collaboration from multiple angles in the presentation today – specifically, tips for pianists in working with singers, tips for singers in working with pianists, and tips for choral educators in working with pianists! As I imagine you’ve all experienced, some collaborations can be extremely rewarding while others leave much to be desired. Often, people struggle with cultivating effective and rewarding collaborations. This can be caused by many things, such as differences in communication style or differences in musical experience and/or ability level with the person (or people) you’re collaborating with. Sometimes it’s not possible to make a collaboration work in the way it needs to, however, I feel that it’s possible to make the best of most collaborative situations! Though much of the information I present today might not be new to you, it is my hope that I help to “refresh” your approach to collaboration as well as offer you tips that you can pass on to your friends, colleagues, and students! I’ll offer ample time for questions and comments at the end of the presentation, so please jot down anything that might come to mind and be sure to mention it when the time comes for questions!

Regarding my own musical journey, I’ve been on quite the windy path. Believe it or not, I majored in both architecture AND piano performance at the University of Idaho. Music had been a part of my life since I began my piano studies at the age of four, but I didn’t think a career in music was viable. Therefore, I had set myself on a track to become an architect! However, my piano professor at the University of Idaho, Jay Mauchley, said that he thought I had what it takes to have a career in music! His belief in me shifted my path entirely and caused me to then pursue Master of Music and Doctor of Music degrees in Piano Performance at Florida State University.

Though all of my music degrees were in solo performance, the bulk of my performing experience has been collaborative in nature. I will always have a passion for solo piano performance and truly feel that studying solo repertoire helped provide me with the technical and musical skills needed to excel as a collaborative pianist. However, I have allowed myself to embrace a life centered predominantly around collaborative piano and feel that my greatest contributions to the musical world are as a collaborative pianist! Throughout our lives, people around us try to put us into different boxes. Though usually well-intentioned, those boxes are informed by the experiences of those people and don’t necessarily reflect the journey that YOU ultimately would benefit from taking. It is from my own experiences in wrestling with my musical path that I come to you today.

II. Qualities of a rewarding collaboration

First, I would like to talk about four qualities/aspects of what I consider to be an effective and rewarding collaboration.

- Clear and respectful communication

- Allowing for openness

- Listening with intention

- Musical alchemy

I’ll now address each of these aspects individually! In terms of clear and respectful communication, you might be thinking, “Well, that’s a given!” However, it’s important not to assume that the way you’re used to communicating will work for whoever you’re collaborating with. Learning to be a good collaborator means learning how to adjust the way you communicate in order for your message to be received clearly and positively. Let’s say that you prefer to receive constructive criticism in a softer, more gentle way. If someone you’re working with then approaches you with blunt constructive criticism, their comments might seem negative or harsh to you. This then causes you to not feel safe in that particular collaborative situation and results in you putting a wall up that gets in the way of achieving a symbiotic working relationship. Conversely, if you’re the one delivering the blunt constructive criticism to someone who prefers a more gentle delivery of feedback, you might notice the other person all of a sudden acting in a defensive manner as opposed to being receptive to your feedback. Developing communication strategies takes a lot of practice, and you’ll be better at it some days than others, however, we are musicians because we desire connection – connection with each other as musicians and connection with our audience! Ultimately, we should strive to develop flexibility with our communication styles which then only helps us to elevate the level of music we’re able to make

Second on my list is “allowing for openness.” By this, I mean surrendering yourself in part to a collaborative situation so that there is room for all parties involved to express themselves authentically and openly. If you go into a collaboration with a fixed view of what you are wanting to achieve and how you are wanting to achieve it, you are then requiring everyone else around you to bend to your ways and essentially change how they would naturally approach the collaboration. However, there is so much to learn from the unique and wonderful ways that other people perceive things which can in turn lead to transformational growth. None of us have the “100% correct” way of approaching music. That’s what’s so beautiful about making music! If we can learn to hold space for the different ways in which other people approach their music making process, it creates a safe space in which everyone feels valued and free to express themselves!

Thirdly, I find that “listening with intention” is incredibly important! As performers, we express ourselves in highly nuanced ways, both in our body language and in how we feel music. When working with singers specifically, I’m able to pick up on subtle details such as the slightest of changes in how a singer is breathing in between two particular phrases or a shift in the emotional quality of the music at any given point. Though I might approach the music in a different way if I were to craft my own personal interpretation, I find it important to tune into another musician’s unique way of feeling the music and adapt my approach to the music in order to best serve our musical partnership. I never take a single moment in a musical collaboration for granted. This allows for a sense of freedom within a performance because I am allowing the other musician room for spontaneity within their interpretation!

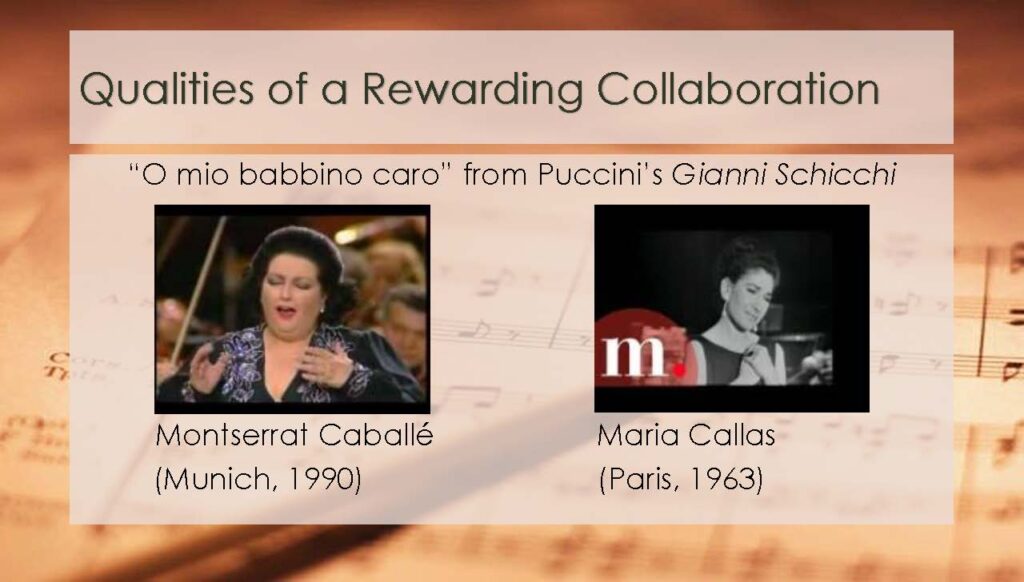

I’d like to now play two short clips of performances of Puccini’s famous aria “O mio babbino caro” from Gianni Schicchi. The first clip is from a performance by Montserrat Caballé and the second clip is from a performance by Maria Callas. (play clips) As you heard, these two performances are quite different from one another. This mirrors my experience in accompanying this particular aria, with no two singers interpreting it in the same way. This aria lends itself to freedom of expression, so I am always prepared to cater my approach to the accompaniment to a singer’s own interpretation. Since I know the general areas where time is usually taken, I can adjust my sense of rubato quite easily depending upon the interpretive choices a singer makes. Lastly, I feel that truly dynamic collaborations allow for “musical alchemy.” Alchemy, in its more abstract sense, is “a seemingly magical process of transformation, creation, or combination [of the two].” This word captures the magic of musical collaboration well, where separate musical parts are woven together to create something greater than any one of the parts could achieve on their own. When all of the aspects of an effective and rewarding collaboration that I just discussed are in place, it can result in quite an alchemical experience. This not only creates a close bond between the performers but also draws the audience closer to the performers, creating an intimacy that stems largely from the trust the performers have built with one another. As performers, we spend so much time focusing on getting all of the correct notes and rhythms. Though this is certainly an important part of the music making process, there comes a time when you just need to trust the work you’ve put in and allow the music to take flight!

III. Tips for Pianists: How to Cultivate Rewarding and Effective Collaborations with Singers

Throughout my time as a collaborative pianist, I’ve worked with a multitude of instrumentalists and vocalists. However, my focus these past several years has shifted to a focus on vocal accompanying. I feel that many people underestimate the difficulty of singing and everything that goes into crafting a compelling performance. In working closely with many singers the past several years, I’ve become skilled at understanding the unique nuances involved with singing which has allowed me to become a more sensitive collaborator! For any pianists here in the room today and for singers who want to understand vocal music more from the pianist’s point of view, the following are aspects of vocal accompanying I feel are important for any pianist to be aware of and grow in their awareness. First off, it’s important to understand the art of singing and the main layers involved in a vocal performance – breath, diction, the conveyance of emotion, and body language. I’ll start in talking about the role of breath in vocal music. So much can be communicated by a single breath that a singer takes. I’m sure you’ve all heard some variation of the saying, “The breath you take determines the sound you make.” With vocal accompanying, I use the quality of a singer’s breath to inform how I support them with the accompaniment. If I notice a singer taking a slow, expressive breath, I try to match and support the emotion conveyed in that breath with whatever I have in the accompaniment part at that moment. Conversely, if I notice a singer taking a quick and excited breath, I then prepare myself to match the energy the singer is communicating to me. The role of vocal accompaniment is to help paint the emotional landscape within which the singer tells their story.

Secondly, I never assume that with a particular song that any two singers will be breathing in the same way! As a result, I make sure to pay close attention to wherever I notice a singer taking a breath in the first few run-throughs of a piece of music to make sure I’m building in the space a singer needs to breathe. I’ll often stop after or even within a phrase to clarify where a singer might potentially be needing a breath. Sometimes, a singer has to play around with breath locations, so it might take a bit of time to lock in that aspect of the music. However, I make a point of discussing this in detail with the singer, as I want them to ultimately feel as much freedom as possible while singing. One example recently of a singer taking a breath in a way I wasn’t expecting was in the famous Mozart aria “Deh vieni, non tardar.” Both times the singer states “Ti vo’ la fronte,” I usually expect a quick breath right afterwards before the word “incoronar.” However, a singer I worked with recently took much longer breaths than I’m traditionally accustomed at these two particular points in the music. She didn’t communicate to me ahead of time that she was going to take extra time with her breaths, but since I’m used to breaths being taken in these spots, I was able to follow her right away and give her the time she needed. If I had been on autopilot, I would’ve beaten her to the word “incoronar.” However, I try never to take a single musical moment for granted and allow for flexibility in how a particular singer might want to interpret a piece of music. The second layer of vocal music I’d like to discuss is diction! One of the most enjoyable things about vocal music to me is getting to explore different languages. In the beginnings of my vocal accompanying journey, I didn’t fully appreciate the nuances of how the text interacts with the melody. Take for instance the language of Italian, where it sometimes baffles me how many consecutive vowels you can squeeze into one single word! In the aria “Ah! mio cor, schernito sei” by Handel, the word “puoi” makes several appearances, which translates to “you can.” Except in two particular spots, this Italian word is set to one single note, with the syllabic emphasis on the vowel “o.” As a result, I make sure to align my accompaniment part with the “o” vowel to reflect the correct pronunciation of the word. When beginning to accompany singers, I often didn’t know how to align my accompaniment with the vocal line in spots where the diction was more complicated. Having a basic understanding of diction in different languages allows me to support a singer more sensitively and fully appreciate the nuances that define one language from another. Third on my list is “emotion,” specifically the conveyance of emotion. Emotion in vocal music can be conveyed in several ways – through facial expressions, through dynamics and the specific way a vocal line is phrased, through diction, through the quality of a breath, and even in through how silence is treated. In paying attention to any of these elements, I am able to gather how to interpret the accompaniment part in a way that matches the emotional intent of the singer at any given moment. Lastly, body language plays a huge role in a singer’s performance! What sets singers apart from instrumentalists is the added responsibility of “acting” and embodying the character being portrayed in a vocal work. An example of a way in which I interpret body language can be seen at the very beginning of a performance. I do not need a singer to look at over at me and nod their head to indicate that they are ready to begin. All I need is to visibly see that the singer has transformed into the character they are about to portray in the music! I’ll talk more about this later on, but subtle physical cues or gestures communicate so much to the pianist. Let’s say that there is a dramatic pause in a piece of music. Simply from visually analyzing a singer’s emotional intention in that moment, I am able to tell when a singer is preparing to enter back in after the pause both from how they adjust their posture or gesture to usher in the next phrase as well as their breath preparation. In understanding these basic elements, I then work as a pianist to develop greater sensitivity and responsiveness while performing. When you start to become aware of the many nuances that define the art of singing, you can begin to cultivate “mind reading” abilities, anticipating a singer’s next move based upon the cues they are giving you (whether they realize it or not)! For example, when a singer increases the speed of their vibrato, that intensification signals to me forward motion. Conversely, when a singer takes a greater amount of time with their diction and in exploring the connections from one syllable to another, that communicates to me a desire to broaden the music. Often, a singer will be wanting to move more quickly, but through the quality of their singing, I end up playing the accompaniment more slowly than they would like. This provides an opportunity to have a conversation about what I’m listening for to inform how I’m interpreting the music. I love moments like this in collaboration as it provides the singer an opportunity to take greater ownership of their music making and truly realize how much power they have to communicate their musical desires and intentions to me in clear, intelligible ways. Next, it is important to hone your analytical skills as a collaborative pianist. So much is communicated in the musical score that can help you to more accurately honor the composer’s intentions. Learning how to see phrases, harmonic progressions, and visually comprehend the musical story being told can help you to embody the character and emotional qualities of a piece of music more quickly. Music largely revolves around the concept of “tension and release,” where there is momentum towards a goal of some sort and then a release after the goal has been reached. Being able to analyze a musical score for this ebb and flow can help you shape the music in a more meaningful way and give it a clearer structure. When I am sight reading, it doesn’t take much time for me to gauge the “vibe” of the music and the overall feel that a composer is going for. This is definitely a result of having accompanied countless works in the vocal repertoire and having a whole mental library of musical patterns to draw from. However, any pianist has the ability to develop this skill. It just takes practice as well as a love and appreciation for vocal music! Finally, it is important to learn how to communicate respectfully when discussing music with fellow collaborators. One of the difficult aspects of collaboration is trying to meld the unique personalities and playing styles of individuals in a way that creates a cohesive and unified sound. When making interpretive decisions regarding a musical score, it is important that all collaborators are on the same page. Communicating ideas and constructive criticism should always be done in a way where everyone feels respected and valued. No two people will possess the exact same communication styles or strategies. However, if a baseline of mutual respect is established from the beginning of the collaboration, it will only help to enhance the overall experience and result in a more polished and impactful performance! We all have blind spots when it comes to various aspects of our musicianship, so it’s important to take that into consideration when offering corrections and/or suggestions to fellow musicians. Mistakes are an inevitable part of the music making process, but they should be seen as opportunities for growth as opposed to sources of guilt.

IV. Tips for Singers: How to Cultivate Rewarding and Effective Collaborations with Pianists

Next, I would like to address collaboration more from the singer’s side of things! The two areas I’ll discuss are how to prepare for a collaboration and how to clearly communicate your musical desires and intentions.

In preparing for a collaboration, be sure to ask the pianist how they prefer the music scores to be provided, whether that’s paper copies or PDF files. If paper copies, ask the pianist how they’d like the paper copies to be formatted. Personally, I’m pretty finicky with how I assemble hard copies of music scores. So, I’ve often asked for single-sided copies of the music so I can assemble the pages in a way that works best for me. However, a safe bet would be for you to provide double-sided copies of the music, hole-punched and inserted in a binder. Make sure that the pages are formatted correctly in terms of which pages should be positioned on the left and which should be positioned on the right. A good hint for this is the page number marking on a page, which should always be on the outer top corner of the page.

In auditions, I’ve often received single-sided copies of music and have struggled to keep the loose pages upright on the piano rack while trying to navigate playing with both of my hands and shuffling pages to the side as I work through the score. I’ve also received double-sided copies that were NOT hole-punched or inserted into a binder. That, to me, is worse than single-sided copies, as you not only have to flip the page around but eventually slide it to the side to get to the next page. I’ve also encountered singers giving me original copies of scores but without considering that the pages won’t stay open on their own. I then have to juggle securing one of the ends of the score with another book and navigate flipping pages that don’t want to stay flipped. If providing the original score, I’d recommend getting it spiral bound. Your pianist will thank you!!

In my own music binders, I mostly have the pages formatted in a left-right fashion. However, I sometimes tape on a flap on the left for the beginning page or a flap on the right for the final page of a piece of music. This helps to eliminate page turns, which trust me, most pianists would appreciate. Lastly, make sure that the accompaniment part isn’t getting cut off on any of the pages. It can be easy to neglect seeing that the accompaniment part is slightly chopped off on the bottom of a page, just because you are used to visually focusing on the vocal line. This has happened to me a fair amount, so I felt it was important to mention.

Now that your pianist has the music in their preferred format (wink, wink), it’s important to come into your rehearsals with a plan. This ensures that you’re making the most of your time with the pianist. Often, a singer has warmed up by the time they arrive for a rehearsal with me. If not, I’ll ask for a singer’s preferred warmups and have them guide me on how far up or down to go. With younger singers, they often draw a blank when I ask them what warmups they’d like to do. Though I can suggest certain warmups, I encourage younger singers to make note of the warmups their teacher uses with them in lessons. That way, they are able to adequately warm up their own voice when not with their teacher and use specific warmups catered to their voice. After warming up, it’s then time to dig into the music! It is so helpful when a singer has clear goals they want to address with their music in any given rehearsal, such as specific parts of songs they’d like to work on. This allows for a much greater amount of progress to happen from rehearsal to rehearsal! I generally have a fair amount of observations to make with any music I’m working on with a singer, and it’s helpful if the singer has studied the music enough to be able to talk about it in a meaningful way. In general, the more a singer is prepared for a rehearsal with me, the more we are able to accomplish!

Next, I’d like to discuss the ways in which a singer has the ability to communicate their musical desires and intentions to me simply through demonstrating them through their singing. The main areas I’ll address are breath, diction, phrasing, and tempo. Regarding breath, the main issue that I understandably run into is singers telling me they didn’t have enough breath to make it to the end of a phrase. This then leads me to think one of two things: does the singer just need to work on breath control more, or might it be necessary to add an extra breath in somewhere? There is NOTHING wrong with needing to add an extra breath in. In fact, it can lead to a more expressive performance and eliminate any anxiety about not being able to make it through the phrase! Context is everything, of course, but at the end of the day, singing should feel free and fulfilling.

For many of my music gigs, I only get one or two rehearsals with a singer before a performance. As a result, we don’t have time to discuss every single breath location. With professional-level singers, I find that they have a way of communicating to me musically that they are approaching a breath which then prompts me to give them the space they are wanting to create. Often, this might take the form of slight rubato leading up to the breath, which immediately causes my ears to perk up. Singers often make their catch breaths abrupt, which communicates to the audience “I’m running out of breath!” However, breathing should always be connected to the storytelling of the music!

Lastly, breath can be used to convey emotion! Less experienced singers don’t always think about how their breath is connected to the emotion they want to convey in the music. Like I mentioned earlier, the quality of a breath, whether quick and energetic or slow and expressive, communicates to me the emotion the singer will be approaching the following phrase with. The breath gives me a chance to then match my energy with the singer’s energy to ensure that we are telling the same story. Giving yourself the time and space to breathe in the emotion you want to convey is important in taking greater ownership of the music. This conveys confidence and maturity to the audience and makes the storytelling all the more convincing!

One of the things I love the most about vocal repertoire is the exposure I get to different languages, which then allows me a glimpse into different cultures and ways of seeing and describing the world! There can be quite a different energetic quality between one language and another, and it’s wonderful to explore these nuances. Regarding music interpretation, the way in which a singer articulates the text at any given point communicates a lot about the emotion the singer is conveying. If I hear a singer exploring the connections between syllables and words in a more intentional and connected fashion, I will match that quality in my playing to support them. Conversely, if I hear a singer being more insistent with the text and making each syllable and word more marked in quality, I’ll match that emotional intensity in my playing. Being really clear with your emotional intent through diction takes a lot of confidence and a willingness to be vulnerable. We often try to make ourselves small as humans, but there isn’t room for that in music. If we’re not convinced of the story we’re telling as musicians, neither will our audience!

Another way a singer can communicate their musical desires to me is through phrasing. I am actively analyzing a singer’s phrasing the entire time I am accompanying them. Just a slight change in the dynamic level or speed of vibrato gives me all of the information I need to shape my playing. When a singer isn’t being intentional with their phrasing, I am then left with the responsibility of guessing what they want. A singer might end up responding to my interpretive choices, but ultimately, it is best if a singer has a clear idea of how they want to shape the music. If they are unclear about how to interpret the music, I’ll then ask questions that help them to think about the music in a more intentional way!

Next, there are many ways in which a singer can communicate the tempo they would like! Sometimes, I inadvertently begin an accompaniment part either slower or faster than a singer desires. If that happens, the singer has the ability to course-correct my playing to establish the tempo they are wanting. If I begin too slowly, a singer can take the reins and enter with greater rhythmic intensity and clarity of diction to communicate to me that they are wanting more forward momentum. If I begin too quickly, a singer can be more broad with the diction and insistent with the rhythm of the opening notes, which then tells me that I need to put on the breaks slightly. Making tempo corrections on the spot takes a lot of trust in the pianist, but it shows that a singer is taking ownership of their music! This is something I rehearse with singers before an important performance so that we are both prepared for any potential tempo issues that might pop up.

Lastly, I’d like to address beginnings and endings of performances. At the beginning of a vocal work, I don’t need a singer to look over at me and nod their head to indicate that they’re ready to begin. Often, it works for a singer to lower their head slightly before beginning and then raise their head as the character they are about to portray. When I can see the singer has assumed their character, I know it’s show time! This goes to show how communicative body language is during a performance. At the end of a performance, it can be awkward to then snap out of your character and acknowledge the audience. Sometimes, a singer’s nerves will kick in and they’ll end up taking a bow without including their pianist. If this happens, it is nice if the singer then tastefully motions over to the pianist to then accept their applause. Ideally, though, it is nice if the singer and pianist bow together. After all, they’re a musical team, and it takes both parts to make the performance possible! When bowing together, a singer doesn’t need to make a grand gesture over to the pianist. I usually suggest a singer just give a few “beats” to allow the pianist to step away from the bench and get in line with them. Once the singer sees out of their periphery that the pianist has stood up and is ready to bow, both musicians can then bow together. Bowing can feel quite awkward to less-experienced singers, however, it gets easier over time! There is so much more I could discuss about the singer-pianist relationship, but for time’s sake, I’ll have to move on.

V. Tips for Choral Educators: Building Strong Relationships with Pianists

The last topic I’d like to briefly address is how choral educators can work to cultivate and nurture strong relationships with pianists. I’ve had the privilege of accompanying for many choral performances, from an elementary-school level all of the way up to a professional-level community chamber choir. Some of the most beautiful music making happens in a choir. The human voice has a powerful ability to connect to a listener’s heart and soul, and when combining multiple voices together, it truly is a magical experience. A pianist is often an unsung hero in a choral performance. Though the focus is understandably on the voices, the piano accompaniment is so integral in helping to paint the emotional landscape within which the singing happens.

First, when looking for a pianist, it’s important to consider that many pianists won’t be available for all the rehearsals you’d ideally like them at. This doesn’t need to be a complete deal breaker, though. Pianists are often in high demand and are juggling many other obligations, so flexibility in scheduling is important.

Once you’ve secured a pianist, it’s important to make sure they’re given the music well in advance of the performance. For a full-length choir concert, at least a month in advance would be advisable for giving the music to your pianist. I understand that emergencies can happen, and sometimes a replacement accompanist needs to be brought in at the last minute. However, sending music sooner than later is preferable, even if you know the pianist is a good sight reader! When sending the music, it is extremely helpful to have the desired tempo markings written in the score as well as any expressive markings that are important for the pianist to be aware of. Additionally, sending links to reference recordings is very helpful and can help get the pianist in the “ballpark” for how you’re wanting to interpret a particular choral work.

Secondly, I’d like to discuss the concept of trust. Some of my most rewarding choral accompaniment experiences have been when I’ve felt trusted by the choral director and acknowledged as a musical partner. One example would be with a choral work that has an extended piano introduction. I love when a choral director will start me off for the first measure or two but then allow me to interpret the remainder of the introduction without it being conducted. This pertains mostly to slower and more expressive choral works, but it can be so powerful and communicates to the audience that the director respects and trusts the pianist enough to grant them freedom. It can be so tempting to want to control every element of the music, but by the time of a performance, you will have likely discussed all of the nuances of the music in great detail. So, why not allow yourself to trust and let go! The same could go for isolated sections where the whole choir is singing. It is powerful as an audience member to see a director sometimes step to the side and allow the choir to take the spotlight in certain spots. This empowers the singers and makes them feel like they can be trusted with the music.

Lastly, acknowledging your accompanist as a musical partner will help to ensure that they feel valued and respected. Collaborative pianists fulfill a supporting role, therefore it is sometimes easy to see them as a “background” or secondary element. Making sure to offer a pianist periodic praise and validation for their playing in front of the choral ensemble can help the pianist to feel more like a musical partner and ensure that they don’t feel like they are being taken for granted. The same can be said for working with the members of your choral ensemble! In the beginnings of any relationship, we all generally make more of a point of showing our appreciation for someone. Over time, our instinct to show appreciation dwindles because we assume the person knows we appreciate them. However, this needs to be a constant part of any relationship, no matter how long you’ve known somebody. It’s like dating someone and only saying “I love you” the first year you’re together but then neglecting to say it after that because you feel like you’ve already established your love for them. Relationships take constant nurturing, and that greatly applies to musical collaborations!

Work to build a solid relationship with your ensemble accompanist, because if they feel valued and respected, it will elevate the music you make together! It also shows the members of your ensemble how important every person is in the music making process. Though some people might have more active roles and others have more of a supporting role, no one person is more important than another. Everyone plays a part in telling the musical story!

VI. Conclusion

Thank you so much for attending my presentation today! As artists, we have an important responsibility to give a voice to the human experience. Collaborative musical experiences can offer such a powerful way to explore what it means to be human. As you go forward with your own various collaborations, I encourage you to be open, lead with your hearts and not your heads, and allow yourself to constantly learn and be transformed by the power of connection. Thank you!